Corpus Christi (Poland), Les Miserables (France), and Honeyland (North Macedonia) are three films all nominated in the International Feature Oscar category. All of these movies examine the difficulties of the underprivileged. As such, it is often difficult to find beauty amid suffering.

But these movies do find it and they also point a damning finger at the oppressive role of authority. We often think that we have an us-versus-them polarity in the United States, but as these movies make clear – the fight against oppression and the inequity of ‘the system’ is being fought everywhere.

“The opening minutes of Honeyland are astonishing – as sublime and strange and full of human and natural beauty – as anything I’ve ever seen in a movie,” wrote A.O. Scott, film critic for the New York Times. Later that year, he called Honeyland the best film of 2019!

The panoramic views of the Macedonian countryside are eerily beautiful portraying a stark kind of beauty. The patient and loving attention paid to the characters, especially the main subject, Hatidze Muratova, are reflected in close-up portraits of a weathered, weary, but persistent face. Detailed pictures of bee life show us unknown sides of these creatures. And all of it is bathed in a soft golden yellow light that seems as if the picture was shot through a lens filled with honey.

The directors, and writers, Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov, had originally set out to do a documentary about environmental issues in their country. But they found Hatidze, and her simple but powerful story captivated them. They spent nearly four years filming over 400 hours of footage following her life as she tends to her bees, and her mother, and sell her honey at the market in a nearby city. There is much to admire here in the simplicity of her relationship with nature and, although she works constantly, she admirably manages to carve out a meager existence, and still have a few moments for laughter.

But then she gains new neighbors who completely upset the balance, not only of her life, but of her relationship to nature. More than an allegory, the neighbors are motivated by capitalistic greed and end up violating the one rule that Hatidze tried to teach them: “Take half, leave half”. The results are catastrophic and paint a damning picture of an economic system that ignores long term effects. (4 Stars)

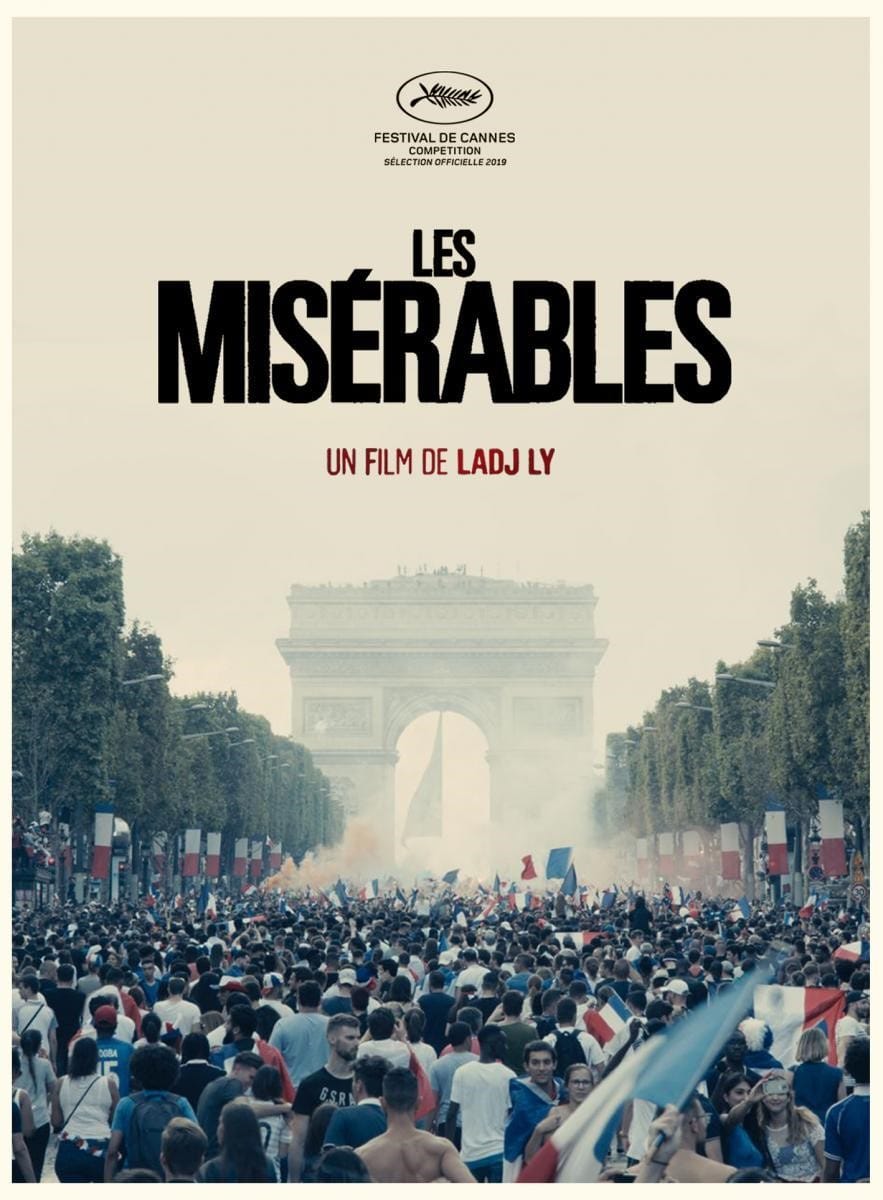

Most people think of a musical when they hear the title Les Miserables, and yes, there have been several versions of the musical on stage and on film. More literate people (not me) have read the massive novel (680,000 words) by Victor Hugo. Written in 1862, it takes place in and around a Paris suburb of Montfermeil, the same one where Hugo lived.

More than 150 years later, that suburb has changed. Today it is filled with public housing projects, full of Paris’s ‘Miserables’, the lower-class black, gypsy, and white communities that have found a complex existence based on neighborhood turfs, local power brokers, and subgroups, including gangs of youth who have, it seems, too much free time and not enough productive things to fill it with.

It is in that neighborhood that director/co-writer Ladj Ly grew up. As a black man, he accidentally filmed an experience with police when he was young and has turned that experience into this movie.

The movie employs several creative elements which, at first, don’t seem all that significant, but cumulatively everything mounts into a thrilling climax. For example, early in the movie, we see shots of the neighborhood from a drone as it flies low over tenement buildings, playgrounds, and city streets. Only later do we see the drone itself and, then, the owner of the drone. This character ends up being a central part of the plot. Other movie highlights include its tight, documentary-like feeling; the camerawork that seems almost like it was filmed from a smartphone; and the economy of the dialog.

And there is no question that the powerful conclusion leaves you gasping. Sheila O’Malley (Roger Ebert) wrote “Les Miserables is a gripping experience, tense and upsetting, showing how seemingly small events, perhaps manageable in the particulars, can balloon into something out of control, like a fire exploding into a conflagration.” It is a conflagration born out of the abuse of power and the mistreatment the citizens receive from the police – sound familiar? (3 Stars)

Corpus Christi has absolutely nothing to do with Texas and everything to do with small-town Polish life and the important role that the Catholic Church plays in structuring and guiding that life.

Daniel has recently been released from ‘juvie’ and moves to a small town to take a job in a sawmill. His first stop on arrival at the town is at the church where he encounters a young woman, Eliza. From there, he slips into telling one little lie after another until he actually takes over from the town vicar and becomes the priest that he always wanted to be, after learning love and forgiveness in jail. Although built on lies and deceptions, Daniel’s transition into Father Tomasz changes both him and the town in many important ways. We watch as his good intentions translate into healing the town in a very significant way – this fraudulent ‘priest’ does more for the town in a few weeks than the legitimate church had done in years. (And along the way, he drinks, smokes marijuana, and sleeps with Eliza – all behaviors that aren’t exactly priestly!)

This isn’t a big movie in any sense of the word, but the film works in so many ways that big-budget Hollywood so often fails to achieve. The script is tight and the editing smart – there is little unnecessary messaging. Most of the movie is filmed through a blue-green filter which has the effect of mellowing the contrasts and accentuating the pain that people feel.

Perhaps the movie’s biggest strength is the lead actor, Bartosz Bielenia. As others have noted, he looks like an incarnation of Christopher Walken right down to the intense blue eyes. His facial expressions suggest the measured moral conflicts he is constantly making as he navigates his way through his fantasy. In the end, he says nothing, but says everything as he exposes his own duplicity.

Daniel succeeds in reconnecting a town desperately in need of it. But, finally, it is the power and authority of the Catholic Church that fails to recognize the goodness that had been done. They reestablished control, but at what cost to the people? (4 Stars).